The use of flash can be controversial in nature photography for a couple of reasons. First, it can disturb the wildlife you’re viewing and second it can affect others trying to photograph the same animal or scene. In fact, some parks and natural areas will prohibit flash photography. Be sure to check with the park rangers or your Expedition Leader to be sure flash photography is permitted. The other controversial part of flash photography is just simply how the resulting photo looks. The animal can look flat, unnatural shadows can appear, and the photo can look a bit fake or contrived. However, when used correctly, flash can be an incredible resource when dim or dark conditions limit our ability to properly photograph an animal or environment. The trick is mastering your flash so that you can use it subtly and preserve the natural look of, well, nature.

When it comes to flash, the adage of moderation is the key to happiness could not be more applicable. New flashes are incredibly powerful and can fully illuminate small birds from 50+ yards away. Despite this feat of human engineering, progress in photo technology does not always equate to getting better photos.

The challenge with flash photography in nature is that a flash coming from a singular point (ie, your camera), is indiscriminant. It lights the surrounding vegetation just as much as it does the subject. Often this can result in shadows that detract from the natural-ness of the scene.

The above photo illustrates the challenge of photographing animals when using flash. On one end, the artificial light provided from the flash allows an impressive depth of field, as shown by the detail and texture on the plant and all parts of the bird here. But on the other hand, the lighting seems a bit…off. The bird and immediate foreground are well lit, but the background is dramatically darker. This is a common problem with bright flash in dim conditions, and is known as the Inverse Square Law.

Inverse Square Law

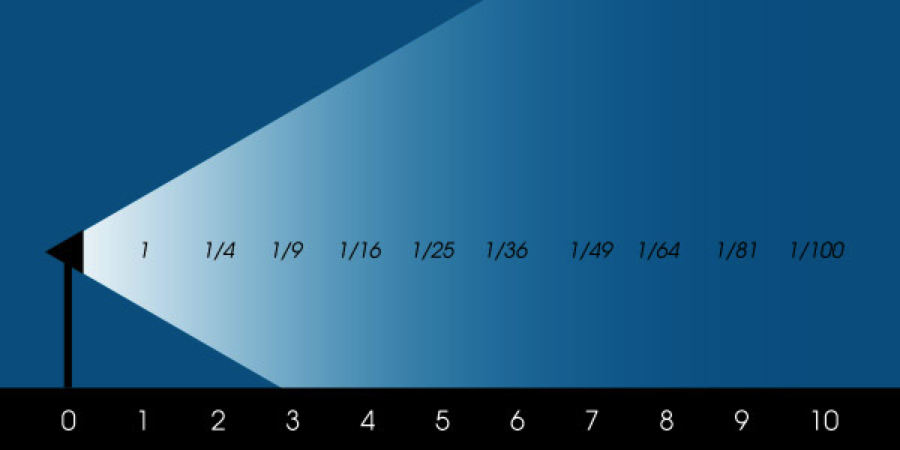

As the distance (measured in meters) from the light increases between flash and subject, the amount of light reaching the subject is 1/distance squared (1/d2). That is, in going from 2 to 4 meters from the subject, you are going from 1/4th to 1/16th of the original amount of light reaching the subject. This is a huge drop off in light and results in dark backgrounds. Don’t worry about the math and the calculations – the main point is that light falls off VERY quickly.

So, the way it affects your photo is simple. If you have a bird in front of some vegetation in the background, the light reaching the bird is much brighter than the background. Even if the vegetation is only a few feet behind the bird, it will be much darker because of this square law and light. If the bird is on a branch and the background is 30 feet away, then the background will be nearly black. This effect is more pronounced when you are photographing something close than when it is far away (because light has already fallen off quite a bit if the subject is far away to begin with).

photography.tutsplus.com

The fact remains that there are times in which you either use flash and get some sort of photo, or you get nothing at all. This is particularly true with wildlife photography at night. The chance of setting up a tripod and keeping the animal still for 5+ seconds to do a long exposure (see Night Photography) is slim to none.

The above photo of a malachite kingfisher is a great example of all we talked about so far. First, you can see that the light falls off dramatically, such that the background is very very dark. In the case of this photo, it actually works quite well with the brilliant blue juxtaposed with the dark black background. So, the effects of light drop off is not always an entirely bad thing.

This is also a great example of when one has no real choice – you either get the photo by using flash, or you get nothing at all. This was taken in very dim conditions at dusk when no camera or lens in the world would have been able to get the shot without flash.

Ultimately, each photographer has their own threshold for how a photo will look with flash or not. The goal here is not to set that threshold for you, but instead to inform you of the major contributors to pushing the limits, and how to avoid doing so.

Being judicious in using flash is the best way to avoid overdoing it, but of course there are always those instances when a photo will look better with more light, or be impossible without flash. Tropical rain forests, dawn and dusk, and macro photography are a few examples of those cases. Learn more about macro photography here.

Controlling your flash

Limiting the amount of light from your flash is achievable in a few different ways. The first way is by mastering the menu system of your flash (if external) or camera (if part of the camera) to manually lessen the output. It’s not as intimidating as it seems, and is usually little more than turning a dial.

The second way is to accessorize. That is, purchase something that goes over your flash to diffuse it and make the light it emits softer and less harsh.

When searching online for flash diffusers, you’ll likely laugh at the variety and simplicity of the devices for sale, ranging from something that seems like a disposable drink cup to a white piece of paper. That’s because diffusers are indeed very simple! You can certainly make one at home, but should you decide to purchase one you’ll be pleased to see that their simple form is matched by their simple price. Most flash diffusers are between 10 and 25 dollars. What you’re paying for is ease – they attach easily and stay put. But, if you’re feeling creative, make one on your own and enjoy.

Like all things commercial, there is the ability to go high end with flash diffusers as well, with moldable versions, different colors, and interchangeable sizes. If the topic of flash diffusion is new to you, start with something basic like the one below, simply slipping on top of your flash and creating nice soft effects.

Or, if you have a pop up flash, carry around a small piece of white plastic or a film canister like the one below and experiment with the results.

The general idea is they spread the light out more evenly so you don’t have one single point of bright white light. Much like clouds help diffuse the sun and lessen harsh shadows, so do flash diffusers. They are not a panacea, and won’t allow you to use flash with impunity for every shot you ever take. But, they are a great item for your “tool kit” in photography in your quest for the perfect shot.

photo.net

Another technique, which you can employ with or without a diffuser, is known as flash bouncing. It sounds like fun – and that’s because it is! The idea is that you are using the flash to illuminate something NOT in the photo, but instead using it’s reflectivity to illuminate your subject more softly.

For example, perhaps there is a white building wall behind you when photographing a bird at the entrance of a nature park. Angle your flash behind you to illuminate the wall, and essentially turn it into one large, diffuse, and less intense flash. If you’ve ever had portraits done of your or your family, you’ll remember large white boxes that would flash when the photo is taken. It’s the same principle – a larger surface will lessen harsh shadows and other undesirables associated with flashes.

However, large white walls are not the only thing to look out for. What about the leaves of a bright spring green tree, or a snow bank? Same thing applies here – aim your flash (obviously needs to be one that you can move, not the ones that pop up on top of your camera) at leaves or snow and have it give you some nice soft lighting, or even incorporating a little green color or side angle to the light!

Flash with macro photography

Macro photography is an entirely different genre of photography, living by different rules in all ways shapes and forms. The use of flash is no exception. With macro photography, a flash is almost a necessity, as you’ll need to set your camera to a wide depth of field (big f-stop number – read the Aperture and F stop section if you have time) to get all the detail and texture that makes macro photography so beautiful.

The above photo of a saturniid moth in Papua New Guinea is a great example of how a seemingly “unphotogenic” little brown moth can turn into something quite fascinating when employing macro photography techniques. This also goes to show you that a macro lens is not necessary to take evocative macro photos. The lens used here was with a kit 18-55mm.

We’ll go into more on macro photo techniques in the Macro photography section, along with more detail on the types of flashes and accessories one can use.

Recap

- Anticipate issues with using flash in nature, both from the wildlife fleeing, as well as fellow photographers becoming a bit grumpy with you. Be sure to ask permission from your guide and fellow travelers before using a bright flash.

- Spend some time getting to know your flash, how to increase and decrease the intensity, and the results by doing different things (ie, angling it to the side or behind you, bouncing it off different surfaces, or using a flash diffuser)

- Moderation is the key to happiness when using flash. If you are using one, always try to take photos with and without flash so that you can compare the results on your computer afterwards.